|

(The unofficial) Yank Archives |

What is Yank? Yank, The Army Weekly, was a magazine published during World War II for American military personnel serving around the world. It was published from 1942 to 1945. Headquartered in New York but distributed in various editions around the world, Yank was written mostly by servicemen. It featured a variety of articles covering everything from news from the homefront to first person accounts from the battlefront. The stories were richly illustrated with photographs and drawings. Yank also included cartoons and photos of pin-up girls and Hollywood starlets.

What is (the unofficial) Yank Archive? This website is an attempt to preserve and make known some of the content of this important historical publication. Our goal is to place searchable excerpts from Yank on the web for new generations to enjoy and for scholarly study by people with an interest in history.

| Most recent articles posted: | ||

| Date posted: | From issue: | |

| Oct 18th, 2011 | Mar 28th, 1943 | |

| They Fight with Film | ||

| The military drafts Hollywood film makers to create films for soldiers. | ||

| Date posted: | From issue: | |

| May 14th, 2011 | Aug 22nd, 1943 | |

| If You're Captured, Button Your ... | ||

| Advice to soldiers on what to expect if captured. | ||

Click here for the article archive

| Advertisements |

The source for fine chainmail.

Chainmail bikinis, jewelry,

and more!

Random Photos |

||

| Click here for the photo archive | ||

Newsbite of the Week |

||

Jan 23rd, 1943: CAIRO — Some neighboring British soldiers passed on this story:

It seems a Tommy lost his bayonet through carelessness and decided to cover the loss by replacing the weapon with one cleverly carved from wood. Things went very well until his company was ordered to fix bayonets. Fearful of baring his wooden substitute, he decided to leave his bayonet sheathed and frantically thought up an answer for the sergeant major who immediately demanded an explanation. Said he: "My good father, on his deathbed several years ago, pledged me not to bare a bayonet on that date henceforth. Today is that date and I honor his dying wish." The sergeant said the story sounded weak and exceedingly fishy, and ordered him to bare his bayonet. Seeing that the jig was up, the Tommy, as he grasped for the handle, muttered in a solemn voice: "May the Good Lord turn the bloody thing to wood." |

||

Click here for the newsbite archive |

|

Article of the Week |

|

From the issue dated Mar 28th, 1943.

Click here for a photo of the article.

Click here for a pdf of the article.

They Fight with Film

Hollywood's high-priced movie experts are now marching to work in privates' and corporals' uniforms, making a new kind of pictures for the Army.

HOLLYWOOD — In a matter of three or four months, the movies will be coming to the fighting zones. This does not mean that Veronica Lake will be functioning as an auxiliary heater in the Nissen huts of Alaska, or that Abbott and Costello will be dangling by their tails from the palm trees of North Africa. It does mean that the Army itself will provide film entertainment and education for U.S. troops everywhere.Films in the front lines are nothing new. The Germans and the Russians have been doing it for a long time. In Stalingrad, for instance, a movie was shown to the Soviet defenders, explaining that their reserves had been sent to the more vital Voronezh front, and that the entire free world was counting on them to hold on. Because they knew why their reserves had been withdrawn, they fought all the harder.

Now the U.S., too, is beginning to divert the great weight of its motion picture industry into G.I. channels. A crack Army film production unit of officers and soldiers now is producing movies exclusively for the Army. Special Service companies attached to every theater of operations already have 16-mm equipment to show these films.

A Typical G.I. Film Program

Based on present schedules, this will be a typical G.I. program:

1) A complete and up-to-date news reel containing more complete material than the civilian news reels at home.

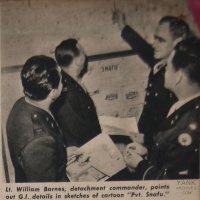

2) A G.I. animated cartoon, "Private Snafu," who is always getting into Donald Duckish complications by forgetting things he is supposed to remember. He even falls into latrines.

3) The story of the American naval victory in the Solomons, told with animated maps and exclusive Navy films.

4) A screen dramatization of the M1 rifle, taken from an article in YANK.

5) A feature film, "Prelude to War," first in a series called "Why We Fight." In this film, Walter Huston, who is the narrator, says, "Why do we fight? What put us into uniform?" Then on the screen, a map of the world splits off into two worlds. One is light, the other dark. Underneath, the following words appear: "This is a fight between a free and a slave world. —Vice President Henry A. Wallace, New York, May 8, 1942." The film shows how in the tortured 1930s these two worlds split apart: our world—the free, and the Axis world—the slave. It shows the invasion of Manchuria, Mussolini's march on Rome, the ascendancy of Hitler, the destruction of the church, murder, assassination, purge, the regimentation of little children.

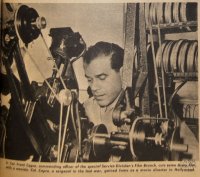

These films are the job of an outfit in Hollywood known as the Film Branch, Special Service Division. It is one of the strangest, most complex outfits in the Army. Its personnel, most of whom are attached to the 834th Signal Company at Fort MacArthur, include some of the best technical brains of Hollywood, now in uniform. There are no movie stars here, no glamor. Just writers and directors; hard-working cameramen, cutters and electricians—now listed as privates, corporals and sergeants. They were the unpublicized backbone of the film industry. And in G.I. camera crews all over the world, they are fast becoming the backbone of the Army's orientation program. Their job, as Gen. Marshall himself explained it, "is to acquaint members of the Army with the principles for which we are fighting." Their job, as their own commanding officer, Lt. Col. Frank Capra, explained it, "is to fight the enemy with cameras as well as guns—to help win the victory of the mind, as well as the victory of the battlefield." Helping them are Hollywood's best civilian writers, directors and producers who work nights for free whenever their services are needed.

They have taken the siesta out of the old orientation lecture, given it the magic of Hollywood.

The first film, "Prelude to War," recently was released experimentally. It was shown to a few high-ranking civilians, and to a few typical Army units. After the civilians saw the film, movie magnates begged the War Department to allow the picture to be shown to the public.

One of the Army units chosen for audition was an Infantry outfit at Fort McClellan, Ala. The men of this outfit marched into the post theater prepared for another orientation lecture on some phase of the war. Some of them, from long practice, fell asleep in their seats before the theater filled. Instead of a lecture, the men saw "Prelude to War." When it was over, they were awake—and applauding.

"Prelude to War" is only one of several dozen films now approaching completion at the studios of the Army's own Film Division. "Prelude" itself is the first in a series, the titles of which have been tentatively listed as:

| Prelude to War | The Nazis Strike |

| The Fall of Scandina- | The Battle of Britain |

| via, the Low Coun- | The Battle of Russia |

| tries and France | The Battle of China |

| America at War | |

These films involve a complicated editing job. The script of each picture is written by Army men who were once among Hollywood's highest priced and most intelligent writers, but they get no individual credits, no publicity in the gossip columns, no interviews in the papers. Then comes the job of getting the proper motion pictures to illustrate the script. Some are historic news-reel clips. Some are hitherto secret captured enemy films. Some are animations made at the Walt Disney studios. Some are production shots, made on location. Some are battle scenes taken by the Film Division's camera crews, or the Navy's expert cameramen anywhere in the world.

Films Portray Allies and Enemies

Second in the list of projects almost completed are two sister series called "Know Your Enemy" and "Know Your Allies." Here, in one film devoted to each, the German, Japanese, Italian, British, Russian, French and Chinese soldiers are taken apart and examined minutely. One little Army production group (writer, director, cameraman, etc.) is assigned to each film.

Here is Hollywood ingenuity at its finest. This is strictly a production job. Each G.I. director is free to use all the tricks at his command. He does. Also he is free to enlist the best of Hollywood civilian talent to assist him anonymously. Thus, don't be surprised if you think you hear the voice of Charles Boyer narrating the French film, or see Greer Garson in the British. It will be their voices, but they ask no credit, and get none, for helping to win the war.

A Screen Version of YANK

There is another series under way, known tentatively as "The Screen Magazine." A new issue of Screen Magazine will be released bimonthly, and will contain two reels of varied G.I. short subjects. It will, frankly, be a screen version of YANK. You will see motion-picture presentations of important YANK features, in addition to exclusive features and interviews which the wandering Screen Magazine camera crews will pick up all over the world. Regular features of the Screen Magazine will be the cartoon, "Private Snafu," and an analysis of the fighting in the war. In short, it will be to YANK what "March of Time" movie short is to Time magazine.

Other individual pictures, worked on independently, round out the present operating schedule of the Army's own Film Division. Typical of these is a full-length feature about officer candidate schools, supervised by Capt. Paul Horgan, the novelist, and directed by two Hollywood directors, Bill Clemens and Ralph Murphy.

Last July, Capt. Horgan was generally minding his business and functioning as a civilian instructor at New Mexico Military Institute. Then he received a message asking him to pay a visit to the War Department in Washington. "Horgan," said Col. Edward L. Munson Jr. of the Special Service Division, "you've had a lot of experience with military education. We'd like you to write us a script for a picture on the Army's OCS system." So Horgan made a swing around the country, visiting all the candidate schools and doing research. Now he's finishing the monumental task, working like mad with two camera crews. When the picture is completed, the Army will dispatch him to duty as an Infantry officer, somewhere in the world.

That's the way the unit works.

Men come and men go. Permanently at the top are Col. Capra, assisted by Maj. Sam Briskin, former general manager of Columbia Studios, as production manager. Less than half of the unit is in Hollywood at any given time. You will find the others wherever there are Army pictures to be made. Maj. Anatole Litvak, for instance, is working under fire with a crew of enlisted men in North Africa right now.

Lt. Col. Warren J. Clear was attached here for a while. He was on Gen. MacArthur's staff and escaped from Corregidor in a submarine, surviving the bloody days of Bataan. Col. Herman Beukema, the great military historian from West Point, was here. So was Maj. Francis Arnoldy, who fought through several campaigns with the French, Russian and American Armies. He was technical advisor on the Russian films. Col. William Mayer, who worked for three years with the Chinese government in bomb-blasted Chungking, assisted on Chinese features.

The enlisted men are old-time Hollywood technicians who were specifically asked to enlist for this job. Most of them are well over 35 and have been working with the studio for years. Some are veterans of the last war, like 45-year-old Sgt. Cecil Axmear, an electrician; or T/Sgt. Jack Ogilvie, who is 44 and works as a cutter; or 45-year-old sound cutter T/Sgt. Charles Gifford, whose oldest son is in the Pacific with the Navy.

Carry Rifles With Their Cameras

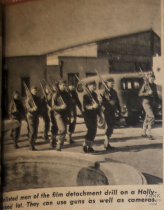

They know their job, which is 1) making motion pictures and 2) fighting. When they go out into the field, they carry full field packs and rifles along with their cameras. When they are in Hollywood, they pull guard duty every five days in addition to their regular work. Three days a week they drill—in the strange setting of a Hollywood lot. They are learning their fighting from experts—Lt. William Barnes, who spent 16 years in the Army as an enlisted man; T/Sgt. Henry Fritsch, the acting first sergeant and head of the research library, who put in several hitches in the National Guard; and M/Sgt. Chester Sticht, a former producer, who served in the Australian Army. They report to their cutting rooms and vaults at 8 A. M., and work sometimes until midnight. Cpl. Cuffe tinkers with his smooth-humming projector, and he knows he is helping to win the victory of the mind. Sgt. McAdam bends over his moviola, and he knows that here Hollywood, stripped of its glamor, is doing its appointed war task.

"We lost the peace the last time," says Col. Capra, a sergeant in the first World War, "because the men of the armed forces were uninformed about what they went to war for—and the nature and type of the enemy they were fighting. None of us here thinks that is going to happen again."

Lt. Col. Frank Capra, of course, went on to make classics like It's a Wonderful Life and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. Many of the other people mentioned in this article can be found on the Internet Movie Database. Many of the movies can be found on You Tube. Just search for the titles.

Your name:

Type this word:

Comment policy: we reserve the right to remove or edit comments that are offensive, off-topic, or contain advertising. Do not use HTML tags in your comment.

| Comments: |

| No comments yet. |

| Home | - | About | - | Articles | - | Photos | - | Newsbites |

© 2012 Yank Archives